Justice Stevens reads the fine print

Before law school, I’d never been on a cruise. Though David Foster Wallace’s famous journalistic argument against cruising had dampened my interest, first-year civil procedure utterly demolished it thanks to Carnival Cruise Lines vs. Shute, 499 U.S. 585 (1991).

First, some legal context. (Along with my usual proviso: though I am a lawyer, I am not your lawyer, and please do not take anything in this piece as legal advice.) Suppose a passenger boards a cruise at a port in the United States. The boat then sails from one destination to another, often among multiple countries, through international waters. This raises two questions: what law applies to the boat and people on it, and where can they bring a legal claim if needed?

For the boat itself, there is a long and boring answer pertaining to the maritime law of the country where the ship is flagged. In the same way that businesses often incorporate in Delaware due to its comparatively lenient rules, cruise ships tend to be registered under foreign flags to avoid expensive US laws (e.g., little things like taxation, wage & labor regulations, worker safety, etc.)

If you’ve ever wondered why there aren’t more cruise ships touring the Hawaiian islands—or why a west-coast US cruise always includes a stop in Mexico or Canada—it’s because under US federal law, a ship that only visits US ports must itself be flagged in the US. This is so economically impractical that there is only one ship so flagged.

But for the passengers, the answer is simple: the ticket is a contract, and these provisions are part of the contract terms. The choice of law provision determines which jurisdiction’s laws apply; the choice of forum provision determines where cases can be heard. And the two may have nothing to do with one another. For instance, the current Carnival terms adopt the “federal maritime law of the United States” and specify that all claims must be brought in federal court in Miami–Dade County, Florida (where Carnival is headquartered, naturally).

Bringing us to Carnival Cruise Lines vs. Shute. Eulala Shute was a resident of Washington state. During her Carnival cruise, she “suffered injuries when she slipped on a deck mat” while sailing in “international waters off the Mexican coast”. Contrary to the choice-of-forum provision in her ticket—printed, of course, in tiny type on the back—Shute filed an injury claim against Carnival in Washington. The court granted summary judgment in favor of Carnival because Shute’s ticket contract required her to file her claim in Miami, and she had not.

On appeal, the Ninth Circuit reversed. It found that requiring Shute to litigate in Miami was unreasonably inconvenient, so the choice-of-forum provision was invalid.

Corporate America squealed in agony. The Ninth Circuit decision would’ve had the precedential effect of forbidding many existing and future choice-of-forum provisions within the Ninth Circuit, which covers about 20% of the US population.

Thus the decision was appealed to the US Supreme Court. The Supreme Court reversed again, restoring the judgment in favor of Carnival. The majority opinion gave more weight to the fact that Shute voluntarily agreed to the choice-of-forum provision. Though the provision made litigation less convenient for her, her inconvenience was offset by other foreseeable benefits. For instance, by consolidating litigation in one place, Carnival could handle injury claims at lower cost, thereby allowing it to reduce ticket prices. (Today, Carnival remains famous for its cheap fares and infamous for its ship disasters.)

Justice John Paul Stevens, however, was not persuaded. He filed a dissent. What was his leading objection? The typography of the ticket:

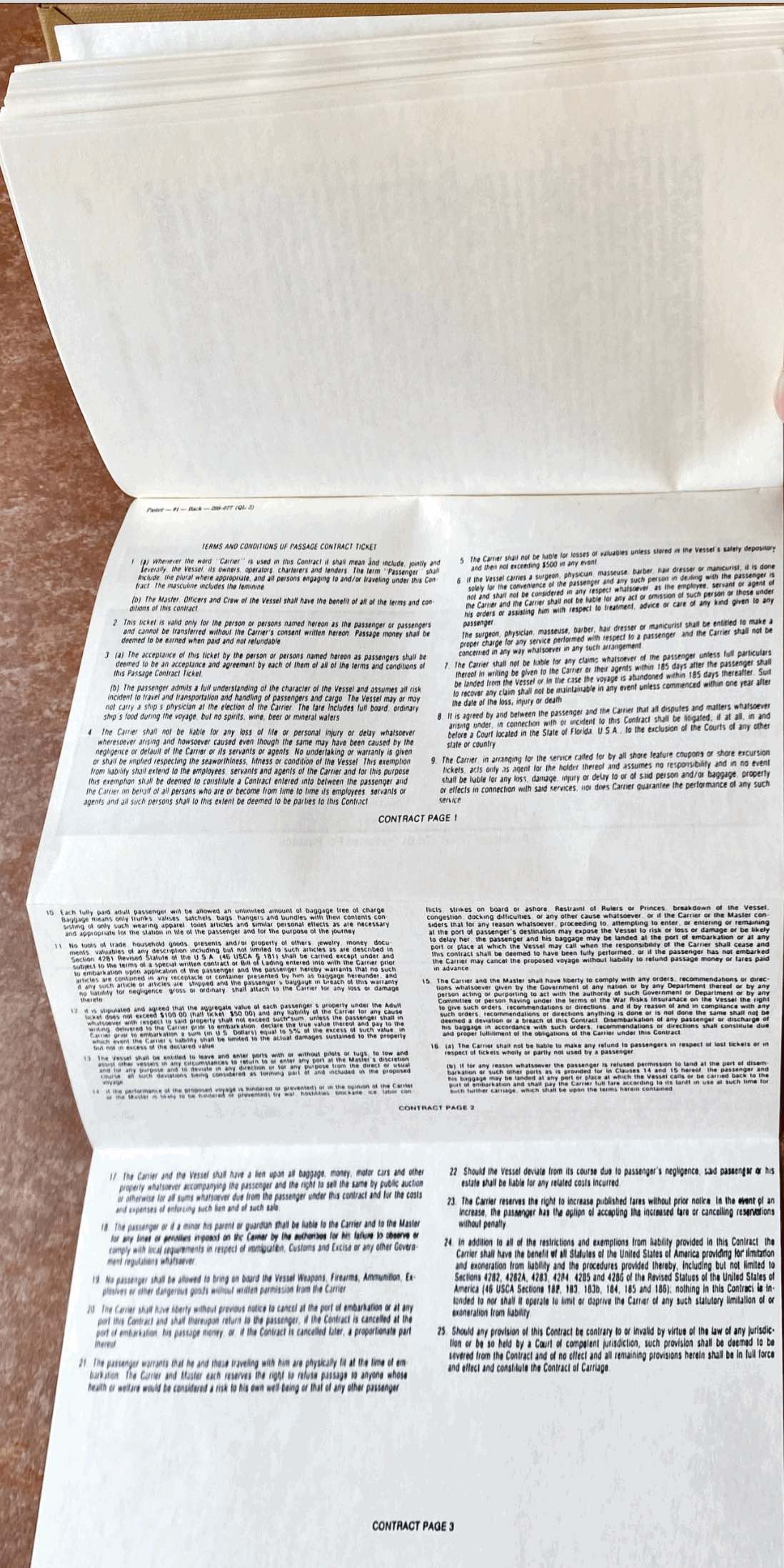

The [majority opinion] prefaces its legal analysis with a factual statement that implies that a purchaser of a Carnival Cruise Lines passenger ticket is fully and fairly notified about the existence of the choice of forum clause … only the most meticulous passenger is likely to become aware of the forum-selection provision. I have therefore appended to this opinion a facsimile of the relevant text, using the type size that actually appears in the ticket itself.

And so we arrive at one of the greatest flexes ever by an Article III judge. If you visit a law library, get volume 499 of the United States Reports from the shelf, and open to the last page of the opinion, you will find the reproduction of the Carnival ticket—actual size, accurately folded—that has since been glued into every copy by order of Justice Stevens.

Was this necessary to make the point? No. Was it arguably a snippy and expensive gesture for a dissent? Perhaps. Nevertheless, I salute Justice Stevens for his empathetic cri de coeur against the lawyerly abuse of fine print.