The collapse of complex societies

Those who criticize so-called “AI doomers” often overlook that there is a broader, intellectually serious tradition of technological doomerism that goes back decades. To revisit these works is to wonder whether AI really presents new risks, or if it is simply the manifestation of a risk previously foretold.

Of course, predictions of global apocalypse are as ancient as humanity. Given the historical track record—no global apocalypse yet!—those predicting apocalypse have traditionally had a rough time being taken seriously. Still, there is a big difference between predicting the arrival of apocalypse ex nihilo vs. a reasoned argument that it necessarily emerges from specific human decisions and habits.

The Limits of Growth

This book, published in 1972, was an early effort to quantitatively model the effects of technological change. I read it some years ago. As the title implies, The Limits of Growth considered how five key global factors would affect human development:

If the present growth trends in world population, industrialization, pollution, food production, and resource depletion continue unchanged, the limits to growth on this planet will be reached sometime within the next one hundred years. The most probable result will be a rather sudden and uncontrollable decline in both population and industrial capacity.

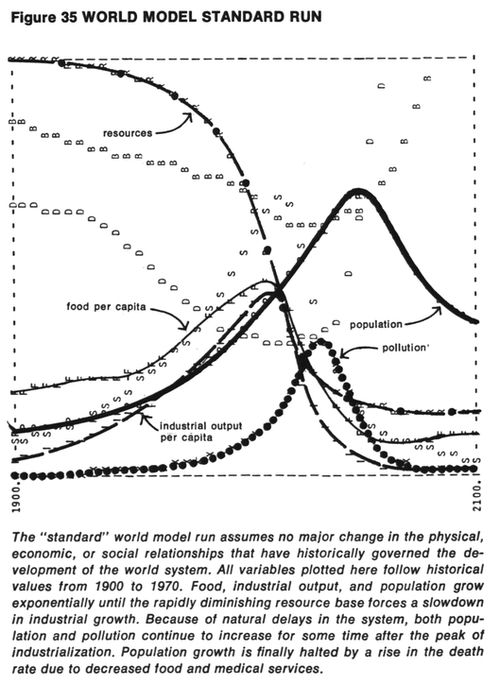

In support of their theories, and unusually for the era, the authors of TLoG relied extensively on software simulations. This allowed the authors to, say, model the course of human progress under realistic current assumptions. In this model, population decreases rapidly after around 2050:

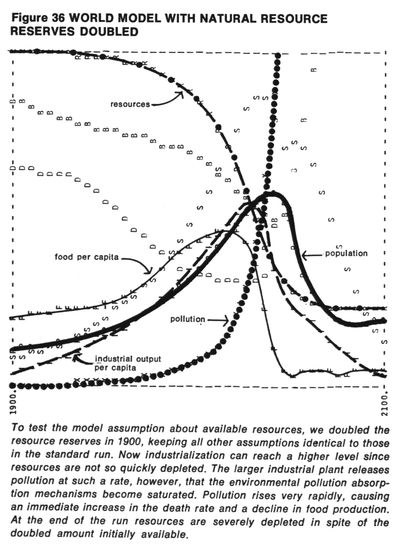

But using a software model also allowed the authors to run simulations with different starting assumptions, such as this one with natural resources doubled. Perhaps counterintuitively, the model predicts that increasing resources causes the big drop in population to happen sooner because uncontrolled pollution negates the benefits of the extra resources:

For 1972, these charts are pretty rad. They remind me of output from programs in my beloved childhood copy of BASIC Computer Games.

Consistent with the usual historical reaction to doomers, TLoG’s methods and conclusions were divisive for decades. The original authors produced multiple sequels: Beyond the Limits in 1992, Limits to Growth: the 30-Year Update in 2004, and Limits and Beyond in 2022. Spoiler: the population still collapses. In the 2023 paper Recalibration of Limits to Growth, a separate group of authors ran the TLoG simulations with updated empirical data. Result? You guessed it.

The Collapse of Complex Societies

This 1988 book, by Joseph Tainter, I read earlier this year. I recommend it—as a work of suspenseful persuasive writing, it’s pretty great. (For those who prefer to preserve the suspense: it’s safe to read this section, but skip the last one.)

Tainter is an anthropologist. His definition of collapse is similar to that of TLoG: “a rapid, significant loss of an established level of sociopolitical complexity.” It doesn’t mean the end of a society, necessarily. Rather, it marks a point after which quality of life tends to get ever worse for ever more people.

But the primary question posed by the book is never said out loud till near the end: is our own society approaching a state of collapse? Might it already be happening?

In contrast to TLoG, Tainter considers collapse retrospectively rather than prospectively. Even though complex societies have only existed for a small fraction of human history, Tainter observes that they’ve nevertheless displayed a strong propensity toward collapse. Why?

Tainter’s theory is straightforward. First, he notes that sociopolitical complexity incurs costs, and that increasing complexity imposes increasing costs. Second, he observes that economists have shown that the principle of diminishing returns is one of the best evidenced in human history—nearly an iron law. Putting these together, Tainter theorizes that societies grow more complex until:

… the increased costs of sociopolitical evolution … reach a point of diminishing marginal returns. … After a certain point, increased investments in complexity fail to yield proportionately increasing returns. Marginal returns decline and marginal costs rise. Complexity as a strategy becomes increasingly costly, and yields decreasing marginal benefits.

Or more colloquially—luxury becomes necessity. Complex societies are thereby forced into a position where an increasing share of their social resources are spent maintaining the status quo rather than investing in future improvements.

(Relatedly, Tainter notes that the perception of childrearing becoming more expensive per generation is not illusory, because investments in complexity that benefit children also tend to increase, imposing a corresponding burden on parents. As an alternative, Tainter mentions a current world society where “[c]hildren are minimally cared for by their mothers until age three, and then are put out to fend for themselves,” apparently by picking up work “in agricultural fields … scar[ing] off birds and baboons.”)

The diminishing return on investment in social complexity does not itself produce collapse. But it puts the society into a state of increasing vulnerability. As its allocation of resources to complexity increases, it progressively loses the ability to cope with the occasional external shocks that complex societies are ordinarily well-adapted to endure (e.g., war, natural disaster, pandemic, etc.) Eventually, with sufficient weakening of the society and a sufficiently dire shock, the society will—inevitably—collapse.

So what does it all mean for us?

Tainter deftly leaves this point aside till nearly the end of the book, having given us readers ample time and clues to consider the issue ourselves.

Tainter agrees with the TLoG authors that we can’t simply grow our way out of the problem through, say, increased research investment, because such research cannot produce substitutes for all forms of social complexity. For instance, research can produce better software that can perform certain tasks more cheaply and thereby reduce organizational costs. But we can’t easily invent entire substitutes for the complex, socially valuable organizations that use the software, e.g.—the military, the judicial system, etc. Furthermore, increasing these research investments would require allocating an escalating proportion of our social wealth, which is already being spent on current goodies we’d rather not relinquish.

But Tainter disagrees with the TLoG authors that economic deceleration or “undevelopment” is an option. Tainter notes that although complex societies are a comparatively recent invention in human history, our planet is currently covered with interdependent complex human societies. Thus, today’s pursuit of social complexity is not only an end unto itself, but also geopolitically competitive. In principle, a nation could choose to decelerate its own economic growth to forestall collapse in the future. But that would simply make itself vulnerable to domination by another nation today. Such deceleration would therefore be politically irrational.

Tainter thus arrives at maximum deadpan:

Collapse, if and when it comes again, will this time be global. No longer can any individual nation collapse. World civilization will disintegrate as a whole. Competitors who evolve as peers collapse in like manner. … It is difficult to know whether world industrial society has yet reached the point where the marginal return for its overall pattern of investment has begun to decline. … Even if [that] point … has not yet been reached, that point will inevitably arrive. … The political conflicts that this will cause, coupled with the increasingly easy availability of nuclear weapons, will create a dangerous world situation in the foreseeable future.

So if you were worried that climate change or AI or cryptocurrency would doom the human race—relax, we were doomed no matter what.

The final page of Tainter’s book offers one productive suggestion, though with a strong sci-fi vibe:

A new energy subsidy is necessary if a declining standard of living and a future global collapse are to be averted. A more abundant form of energy might not reverse the declining marginal return on investment in complexity, but it would make it more possible to finance that investment …

Here indeed is a paradox: a disastrous condition that all decry may force us to tolerate a situation of declining marginal returns long enough to achieve a temporary solution to it. This reprieve must be used rationally to seek for and develop the new energy source(s) that will be necessary … This research and development must be an item of the highest priority, even if, as predicted, this requires reallocation of resources from other economic sectors. Adequate funding of this effort should be included in the budget of every industrialized nation (and the results shared by all).

In other words, humanity can postpone—though not avoid—its big global collapse by collectively choosing to make massive economic sacrifices to fund the development of transformational energy technology. Or, I suppose, some software device that can itself invent the energy technology.

Any ideas?

PS—the most realistic artistic depiction of collapse

Children of Men, about which more later.

update, 150 days later

Collapse OS, a project that intends to preserve the ability to compute post-collapse.